Ira Hayes- Pima Native American and National War Hero

[19]

Ira Hamilton Hayes was born on January 12, 1923, to Nancy Hamilton and Joseph Hayes, a veteran of the Great War. Hayes was of the Pima Indian Tribe and resided on the Gila River Reservation located near Sacaton, Arizona. Ira was the oldest of six children who were supported by his father’s, hard work harvesting cotton and farming.[1]

In 1942, after completing two years of high school, and served in the Civilian Conservation Corps in May and June of 1942, afterward working as a carpenter. On August 26, 1942, young Hayes enlisted in the Marine Corps, Reserve at Phoenix for the duration of the declared National Emergency.[2] following in his father’s footsteps. After he completed basic training in San Diego, California, he was assigned to be trained as a Marine Paratrooper at Camp Gillespie Marine Corps Base located near San Diego and completed his training on November 30th of the same year, earning his silver wings and the nickname, Chief Falling Cloud. He soon joined Company B, 3rd Parachute Battalion, Divisional Special Troops, 3rd Marine Division at Camp Elliot, California, and was promoted to private first class.

On March 14, 1943, Private Hayes sailed for New Caledonia, the next month his unit was redesignated to Company K, 3rd Parachute Battalion, 1st Marine Parachute Regiment and spent a total of eleven months in the Pacific where he fought in the battles of Vella Lavella Island and Bougainville Island.[3] Around the time he returned to San Diego in February of 1944, the parachute units were disbanded, and Ira was transferred to Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28thMarines of the 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California. It was in September of the same year that Hayes sailed to Hawaii with his company to complete additional training. In 1945, less than one year after he moved to Hawaii, on January 1945 Ira left for Iwo Jima along with 70,000 of his fellow Marines as part of the United States push towards the Japanese Mainland. Private First-Class Hayes and his brothers in arms landed on the island in time to take part in the Battle of Iwo Jima, D-Day[4]*, and were stationed in the Pacific theater until March 26th.[5]

Private Hayes’s involvement in the Battle Iwo Jima was the propelling force that would cause his name and the famous image of he and five other United States Service Men to be forever immortalized in the hearts and minds of Americans. It was on February 23, 1945, at the age of 22, Hayes and five other sailors raised our great nation’s sacred flag, “Old Glory”, on the summit of Mount Suribachi, the highest point on the island of Iwo Jima. Private Ira Hayes battled the Japanese Imperial Army until the island was finally secured on March 26th of that year and Hayes’ division, the 5th Marine Division suffered a great number of casualties during the battle of Iwo Jima. Once the fighting had ceased, PFC Hayes was able to return to Hawaii and secure a flight back to the continental U.S on April 15. Just, four days later Hayes joined Company C, 1st Headquarters Battalion, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C. Sometime later, Ira was ordered to return to his former regiment, the 28th Marine Regiment stationed in Hilo, Hawaii, then rejoining Company E of the 29th Regiment. Only three weeks later, on June 19, 1945, he was promoted to corporal. On September 22, 1945, now Corporal Hayes and the rest of Company E departed for Sasebo, Japan to take part in the occupation of Japan.[6]Corporal Ira Hayes sailed home from Japan for the last time on October 25, landing in San Francisco on November 9th. He was honorably discharged less than one month later on December 1st. For his service to his country and his “meritorious and efficient performance of duty while serving with a Marine infantry battalion during operations against the enemy on Vella Lavella and Bougainville, British Solomon Islands, from 15 August to December 1943, and on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, from 19 February to 27 March 1945.”, Corporal Hayes received a Letter of Commendation with Commendation Ribbon by the Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Lieutenant General Roy S. Geiger.[7]Corporal Hayes also received numerous decorations and medals including, the Commendation Ribbon with “V” combat device, the Presidential Unit Citation with one star, which recognized his involvement in the Battle of Iwo Jima, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with four stars, which recognized his involvement in the battles of Vella Lavella, Bougainville, Consolidation of the Northern Solomons and Iwo Jima. He also received the American Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal.[8]

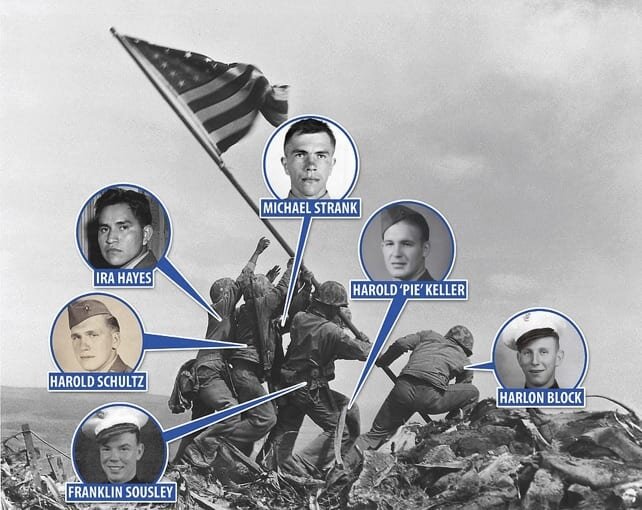

The famous photograph by Associated Press photographer, Joe Rosenthal, titled Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jimasoon became a symbol of the American victory in the Second World War. Corporal Ira Hayes and another marine Rene Gagnon, who was later found to have been incorrectly identified as one of the flag raisers, were hailed as national heroes.[9] Decades after the war, historians discovered the true identity of the man who was previously believed to be Pfc. Rene Gagnon. It was found that the true identity of the man was Cpl. Harold P. Keller, who passed away in 1979 having never told his family about his part in the flag raising. In 2016 historians again discovered the correct identity of another man in the photograph. A group of amateur historians raised questions about the identity of Navy Pharmacists’ Mate 2nd Class John Bradley. A Marine Corps panel discovered that the Marine in question was not Bradley, but was in turn, actually Pfc. Harold Schultz of Detroit, Michigan.[10]

Following the war, Ira Hayes made many public appearances and was revered by the public for his service in the war. Even with all the distinctions and recognitions, he was given Private Hayes was never felt comfortable in the spotlight and did not feel that he should be honored above any of his fallen brothers in arms.[11] On November 10, 1954, the United States Marine Corps War Memorial was unveiled at a special dedication ceremony in our nation’s capital. The then-president of the United States, President Dwight D. Eisenhower recognized and praised the then 32-year-old Pima Marine for his service and dubbed him “a national war hero.”[12]

Tragically, like many of our nation’s veterans, Ira Hamilton Hayes was greatly troubled by the events of the war and was stricken with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and survivor’s guilt. Just ten short weeks after the dedication ceremony of the United States Marine Corps War Memorial, Ira passed away near his home in Sacaton, Arizona at the age of 32. Corporal Ira Hamilton Hayes was laid to rest on February 2, 1955, in Arlington National Cemetery in Section 34, Plot 470A, along with the roughly 400,000 service members that are now buried there.[13] As Corporal Ira Hayes’s body lay in the Phoenix, Arizona mortuary, awaiting burial, his likeness was captured in death. It has been discovered that someone secretly cast a plaster death mask without the family’s knowledge. It wasn’t until recently that the Hayes family found out about the death mask. One of Ira’s brothers, Kenneth Hayes, was able to retrieve his brother’s final image from the Gilbert Ortega Museum Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, where the mask had been on display for many years. Having now retrieved the object, the family laid it to rest, allowing Corporal Ira Hayes’s spirit to travel to the new world. Hayes great nephew, Larry Cook explains that in Pima culture when one passes, everything you owned is to go with you. So, because the death mask was not buried with his body, Ira’s spirit is still lingering. Cook and his wife reveal a short one-page document explaining how the mask came to be. According to the document, which was written and notarized by Shirley Nelson in 1986, it is explained that an artist from Phoenix, Arizona, Hortense Johnson was allowed into the funeral parlor and made a cast of Hayes’s face to preserve history. She intended to make a bust of Ira, but she passed away from cancer before she could do so. The mask was then given to Shirley Nelson and her mother by Nelson’s husband as he knew that they understood what it was, and he was otherwise going to throw it out. Nelson inherited the mask after her mother died and it stayed in a cupboard for years because it frightened her Navajo foster son. In the 1980s, the mask was given to a Navajo artist, Yellowhair, who wanted to make a sculpture of Hayes for the United States Marine Corps. However, Yellowhair never made the sculpture. Around the year 1995, he took the mask to a well-known owner of Native American art and jewelry stores, Gilbert Ortega Sr. The exact nature of the agreement is still unclear, but the mask was now in the possession of Ortega Sr., though Yellowhair still urges that he is the owner and only loaned the mask to Ortega. Ortega Jr, the former’s son, declares that his father did not take objects on loan. In 1999, it was understood that tribal leaders had learned of the mask and became concerned but did nothing to obtain the mask. It took decades for the issue to be taken up again by tribal leaders and finally family members. Larry Cook and his great uncle, Kenneth Hayes, reached out to Ortega Jr., who turned over the mask as a donation to Ira’s descendants. Hayes’s death mask was taken back to the Gila reservation in a matter of hours and a private ceremony was held close to the graves of Corporal Hayes mother and father. The mask was crushed into bits and buried with no marker or monument so that Ira could finally be at peace.[14]

Ira Hayes’ memory has been immortalized through the musical talents of songwriter Peter La Farge and legendary musician Johnny Cash in the Ballad of Ira Hayes.[14] His memory has also been preserved through various other works such as the poem by Marsha Burks Meghee titled (The Ghost Of) Ira Hayes[15], which describes Ira’s heroism and parallels it with the heroism of the first responders of 9/11. Other works that tell of the bravery of Corporal Ira Hayes include Quiet Hero: The Ira Hayes Story by S.D. Nelson and Ira Hayes, Pima Marine by Albert Hemingway. Corporal Hayes’ struggle with PTSD, suddenly being thrust into the public eye and, leaving his brother’s in arms behind are all depicted in the biographical 1961 film The Outsider, starring Tony Curtis.[16]

Corporal Ira Hamilton Hayes, Pima Indian, United States Marine, and National War Hero. Numerous Native American’s that have shown great feats of bravery and sacrifice, paved the way for equality, and have made discoveries and inventions that have greatly impacted our lives have been largely forgotten, Ira Hayes is just one of the numerous indigenous men and women who gave their lives to pave the way for future generations. Let Us Never Forget his sacrifice and bravery.

* D-Day is often used in connection to Operation Overlord, the combined effort of allied forces during the Second World War to invade Nazi occupied France and free France and the French people. However, the term D-Day is a military term used to mean the day that an operation is set to launch or begin. So, D-Day is also used when referring to “Operation Detachment”, which was the largest combat deployment of United States Marines in history. On February 19, 1945, Marine Major General Harry Schmidt was in command of the V Amphibious Corps, which was primarily made up of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Marine Divisions. [4]

Country Legend Johnny Cash singing The Ballad of Ira Hayes

A clip of the 1961 movie The Outsider dedicated to Corporal Ira Hayes, starring Tony Curtis

Left to Right: Photograph of Corporal Ira Hayes of the United States Marine Corps, Pharmacists Mate John H. Bradley of the US Navy and Private Rene Gagnon of the US Marine Corps. (Photograph taken by AP staffer Joe Rosenthal)[18]

Picture/Graphic created to show the correct names and locations of the U.S Service Men raising the flag on Mt. Suribachi at the Battle of Iwo Jima. [20]

Photograph of Ira Hayes and other United States Service Men atop Mt.Suribachi, where he and five others raised the American Flag during the Battle of Iwo Jima. (Cpls. Hayes is on the far left of the photo, holding up his helmet)[17]

[1] Albhasic. (2019, November 20). Ira Hayes: Immortal Flag Raiser at Iwo Jima (1147399282 863096399 M. Cannon, Ed.). Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/68545/ira-hayes-immortal-flag-raiser-iwo-jima

[2] Albhasic.

[3] Patterson, M. R. (2001, May 20). Ira Hamilton Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/irahayes.htm

[4] Alexander, J. (2018, February 17). The Battle of Iwo Jima: A 36-day bloody slog on a sulfuric island. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.militarytimes.com/news/2018/02/17/the-battle-of-iwo-jima-a-36-day-bloody-slog-on-a-sulfuric-island/

[5] Patterson, M. R.

[6] Marine Corps University. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/People/Whos-Who-in-Marine-Corps-History/Gagnon-Ingram/Corporal-Ira-Hamilton-Hayes/

[7] Patterson, M. R.

[8] Marine Corp University. (n.d.).

[9] Mcfetridge, S. (2019, October 17). Marines correct ID of second man who raised flag at Iwo Jima. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://apnews.com/article/95f62df02d7944b28af63636af933a76

[10] Mcfetridge, S.

[11] Albhasic.

[12] Albhasic.

[13] Marine Corps University. (n.d.)

[14] Wagner, D. (2009, December). Death mask of WWII hero Ira Hayes finally buried with legend. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.indiancountrynews.com/index.php/news/education-life/8049-death-mask-of-wwii-hero-ira-hayes-finally-buried-with-legend

[15] JohnnyCashVEVO. (2019, August 29). Johnny Cash - The Ballad of Ira Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEwSwQtSmDQ

[16] Meghee, M. B. (n.d.). (The Ghost Of) Ira Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from http://www.wrensworld.com/irahayes.htm

[17] Arlington National Cemetery. (n.d.). Prominent Military Figures. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Notable-Graves/Prominent-Military-Figures

[18] Clio. (2008, November 28). Ira Hayes: Person, pictures and information. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.fold3.com/page/83002495/ira-hayes

[19]House, R. (2018, February 23). Iwo Jima: The story behind Alan Wood and the famous flag on Mount Suribachi. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/2018/02/23/iwo-jima-the-story-behind-alan-wood-and-the-famous-flag-on-mount-suribachi/

[20]United States Marine Corps202. (2002). Photograph/portrait of Ira Hayes in his U.S. Marine uniform. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/histphotos/id/19429/

[21]Iwo Jima Memorial Midwest Project. (2015). Iwo Jima Memorial Midwest. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.iwojimamemorialmidwest.org/flag-raisers/

Sources

Albhasic. (2019, November 20). Ira Hayes: Immortal Flag Raiser at Iwo Jima (1147399282 863096399 M. Cannon, Ed.). Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/68545/ira-hayes-immortal-flag-raiser-iwo-jima

Alexander, J. (2018, February 17). The Battle of Iwo Jima: A 36-day bloody slog on a sulfuric island. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.militarytimes.com/news/2018/02/17/the-battle-of-iwo-jima-a-36-day-bloody-slog-on-a-sulfuric-island/

Arlington National Cemetery. (n.d.). Prominent Military Figures. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Notable-Graves/Prominent-Military-Figures

Clio. (2008, November 28). Ira Hayes: Person, pictures and information. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.fold3.com/page/83002495/ira-hayes

Flundari. (2018, September 27). Outsider, The 1961 Movie Clip Ira Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://youtu.be/Bz_Ec_s3iWM

House, R. (2018, February 23). Iwo Jima: The story behind Alan Wood and the famous flag on Mount Suribachi. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/2018/02/23/iwo-jima-the-story-behind-alan-wood-and-the-famous-flag-on-mount-suribachi/

Iwo Jima Memorial Midwest Project. (2015). Iwo Jima Memorial Midwest. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.iwojimamemorialmidwest.org/flag-raisers/

JohnnyCashVEVO. (2019, August 29). Johnny Cash - The Ballad of Ira Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEwSwQtSmDQ

Mcfetridge, S. (2019, October 17). Marines correct ID of second man who raised flag at Iwo Jima. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://apnews.com/article/95f62df02d7944b28af63636af933a76

M. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/People/Whos-Who-in-Marine-Corps-History/Gagnon-Ingram/Corporal-Ira-Hamilton-Hayes/

Meghee, M. B. (n.d.). (The Ghost Of) Ira Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from http://www.wrensworld.com/irahayes.htm

Patterson, M. R. (2001, May 20). Ira Hamilton Hayes. Retrieved January 08, 2021, from http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/irahayes.htm

United States Marine Corps202. (2002). Photograph/portrait of Ira Hayes in his U.S. Marine uniform. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/histphotos/id/19429/

Wagner, D. (2009, December). Death mask of WWII hero Ira Hayes finally buried with legend. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.indiancountrynews.com/index.php/news/education-life/8049-death-mask-of-wwii-hero-ira-hayes-finally-buried-with-legend